Information provided on this page is far from an exhaustive list of all the diseases, pests, environmental stressors, and other factors that may diminish tree health. It’s our hope that these resources will serve as an introduction to present and emerging threats that trees in Novi may face.

A good first step toward diagnosing potential problems is knowing what species of plant you’re examining, as many diseases or pests specifically affect just one or a small handful of species.

Click the topics below to expand information on each one.

Girdling roots are roots that encircle the trunk or other roots of a tree and choke off the flow of water and nutrients. This can lead to stress, dieback, and ultimately the death of the tree.

These roots can often be traced back to improper planting technique. Simple planting mistakes may not manifest as problematic girdling roots for many years, however, and by that point it may be too late to correct the damage. That’s why early detection of girdling roots is vital. A trunk that doesn’t flare out near the ground is a good indicator that a tree may be dealing with girdling roots just beneath the surface. If the tree looks like a telephone pole entering the ground, gentle excavation around the base of the trunk may reveal potential problems.

If a small girdling root is still developing, it may be an opportunity to cut it away and prevent it from causing long-term damage. That said, large girdling roots should not be removed in all cases, as it may cause significant damage to the tree and impact its ability to anchor itself to the soil.

To avoid girdling roots when planting trees:

- Cut away, loosen, or straighten circling roots, especially if planting a containerized or balled and burlapped tree.

- Dig a wide planting hole at least three times the size of the root system. Scrape or scratch into the sides of the planting hole to loosen the soil and prevent a “glazing” effect, which may eventually deflect roots.

- Ensure that the tree is planted at the proper depth—the root flare must be visible even after the ground has settled.

- Do not apply more than three inches of mulch and ensure that it is not piled directly against the trunk. “Volcano mulching” is a common and harmful mistake that can lead to girdling roots and other issues.

To correct existing girdling roots:

- Remove excessive soil or mulch so that the root flare is exposed.

- If a girdling root is found and it is two inches in diameter or less, use a small saw or a mallet and chisel to cut away several inches of the girdling root where it makes contact with the trunk.

- If a girdling root that is larger or has grafted with the trunk is found, removal is not always the best option. Residents struggling with large girdling roots should contact an arborist for advice specific to their trees’ needs.

Trees can have too much of a good thing and excessive mulch—especially when applied incorrectly—is a very common and harmful example.

Mulch is organic matter spread around the base of a tree to hold moisture, moderate soil temperature extremes, and reduce grass and weed competition. Common mulches include leaf litter, pine straw, shredded bark, peat moss, or composted wood chips.

A 2 – 4-inch layer of mulch is ideal. More than four inches may prevent air and water from reaching the tree’s roots, particularly in a light rain. Piling mulch right up against the trunk of a tree may cause decay of the living bark, so a mulch-free area 1 – 2 inches wide at the base of the tree can reduce moist bark conditions and prevent such decay.

When mulch is piled up directly against the trunk’s bark, it is commonly called volcano mulching because of the appearance of the pile. Unfortunately, even professional landscaping companies frequently apply too much mulch or volcano mulch their clients’ trees each spring. Over time, these harmful practices stress trees, increase decay and likelihood of tree failure, and can even kill trees.

Even mature trees that have suffered through poor mulching practices for years, however, can be helped by correcting past mulching mistakes. Exposing the tree’s root flare by carefully excavating around its base and reducing the amount of mulch to that ideal 2 – 4” layer can quickly improve the tree’s growing conditions.

During the fall, male deer scrape trees to scrape the velvet off their antlers and to mark their territory and intimidate other bucks with the scent they leave behind.

A tree may be scraped by more than one deer as they come upon a previously scraped tree, to leave their own mark. These scrapes can cut through the thin bark down to the wood, cutting off the cambium, which is the tissue that carries fluid and nutrients from the leaves to the other parts of the tree. The scrapes leave the tree more vulnerable to disease, decay, or pest infestation.

Trees with soft, smooth bark are especially prone to significant damage. If as little as 1/3 of the tree’s circumference is removed, it can start a slow death for the tree. Younger trees’ bark is typically thinner and smoother, so it is especially important to protect them. Both deciduous and evergreen trees may be scraped.

The easiest way to protect your tree is to put a tree guard around the lower four feet of the trunk. The best tree guard is one that allows air to circulate around the trunk. A flexible mesh deer guard is highly recommended, and the sooner you can get it on the tree, the better. They are available online and many hardware and garden stores.

Most herbicides (“weed killer”) work by entering the plant through the leaves. So if tree bark gets sprayed, or encounters some runoff chemical, most herbicides can’t get through the bark and into the tree unless it has very thin bark. Most herbicides also become deactivated once they make contact with soil. This is the recommended type of herbicide—something that only interacts with green, aboveground tissue.

Most herbicides (“weed killer”) work by entering the plant through the leaves. So if tree bark gets sprayed, or encounters some runoff chemical, most herbicides can’t get through the bark and into the tree unless it has very thin bark. Most herbicides also become deactivated once they make contact with soil. This is the recommended type of herbicide—something that only interacts with green, aboveground tissue.

However, there’s been a big push for faster-acting, longer-lasting herbicides, so soil-active chemicals like Imazapyr/Imazapic acid/etc. have been added for those effects. Unfortunately, these herbicides are not deactivated by soil, so they can penetrate the ground and be taken up by tree roots and then damage trees. Even if not applied directly to the tree, these chemicals can get into the ground as run-off and affect trees several feet away or across property lines.

Because of the variety of herbicides readily available to homeowners and the significant impacts they can have on plants and the wildlife that rely on those plants, getting educated on the chemical options—and whether they’re really necessary—should be a priority.

Residents outsourcing such work should discuss herbicide use options with their landscaper and insist that they use something without Imazapyr chemicals if they do determine that chemical treatment is absolutely necessary.

Trees living in an urban environment face several unique challenges that their counterparts growing in forests never encounter. One of the most obvious and impactful examples is nearby construction, and its damage can come in many different forms.

Trees living in an urban environment face several unique challenges that their counterparts growing in forests never encounter. One of the most obvious and impactful examples is nearby construction, and its damage can come in many different forms.

A freshly poured driveway, new sidewalk, or a recently expanded patio are common sights adjacent to struggling trees. That’s because the digging, trenching, or grading required for these types of construction projects destroy the roots of nearby trees and/or change water availability and soil conditions.

Contrary to what many believe, tree roots are not especially deep in the ground, especially in urban areas with compacted soil. The vast majority of Novi’s tree roots are within the top 1-2 feet of soil. Not only can these roots be damaged during the course of digging, but the fine roots—which handle the majority of water and nutrient absorption—can be killed by heavy equipment or materials being driven over top of them.

Large machinery operating too close to trees can also damage branches and trunks if they’re struck, or by hot exhaust fumes. Likewise, any heavy pollutants released during construction may impact tree health.

Trees usually don’t show signs of decline due to construction damage immediately. It may take 1-2 years for the damage to manifest as symptoms.

Proper precautions should protect, at minimum, the tree’s Critical Root Zone (CRZ) during construction. The CRZ is an area around the tree that should stay free of any construction operations in order to preserve its health. It’s determined by the diameter of the tree trunk in inches, which corresponds to the number of feet of CRZ. For example, a 14-inch diameter tree has a CRZ extending 14 feet in every direction from the trunk.

The most immediate impact from construction damage is the loss of roots and ensuing loss of water absorption capacity. If trees are damaged during construction, they should receive additional water while the root system recovers. Tree irrigation may also need to be changed if the grade around the tree changes and it’s now receiving more or less water during rains because of the ground’s slope.

Trees move water from their roots, through their trunks and branches, and out through their leaves in a process called evapotranspiration. As water evaporates from the leaves through specialized structures called stomata, negative pressure is created in the tree’s vascular system, which pulls more water up from the ground. In times of drought, though, available water in the soil becomes scarcer.

Shorter term droughts may cause leaves to wilt, discolor, or drop from the tree. New leaves may be smaller than usual and the tree’s growth rate may slow.

Longer droughts can cause more serious harm, though. Branches may begin to die back from the tips and top of the tree (as water travels the farthest to reach the tree’s extremities). The tree’s wound response and defense against disease and pests will also be reduced under drought stress, increasing the likelihood of comorbidities.

Some species are more tolerant of drought conditions than others and larger trees with a more expansive roots system can access more water than young trees. Drought stress is very common with recently planted trees. Proper watering practices can help keep trees of any size healthy in the face of drought.

Shallow and frequent waterings from irrigation systems designed for turfgrass will do little to help quench tree roots. Trees prefer deep and more infrequent watering. They should get about one inch of rain and/or irrigation per week, which should be concentrated around the dripline of the tree where the greatest density of fine, absorbing roots lie. During periods of drought and/or extreme heat, the tree may benefit from additional water.

Long, vertical (and oftentimes audible) cracks in tree bark that POP open during cold snaps in the winter are likely frost cracks. Thin-barked trees, like young maples, lindens, sycamores, and more, are susceptible to frost cracks—especially if they’re growing in an area exposed to wind and sun (like most of Novi’s street trees).

Frost cracks are most likely to occur on the south or west face the trunk, where the most sun is directed throughout the day. As the sun warms the bark, the plant cells start to expand. Then, once the sun goes down and the temperatures drop rapidly, the plant cells contract rapidly. This rapid contraction can cause the bark to pull apart, leaving a crack or seam and exposed wood behind.

While they’re unlikely to cause long-term problems with otherwise healthy trees, frost cracks should be monitored to ensure they’re sealing properly before decay sets into the exposed wood. Wraps or sealants should NOT be applied to frost cracks, as these are detrimental to the tree’s compartmentalization process. Instead, ensure the tree is receiving sufficient water and nutrients throughout the growing season to support its recovery.

Leaves turning yellow intermittently throughout the crown of a tuliptree—sometimes with black or brown spots—is the sign of tuliptree leaf drop. This phenomenon is generally not a cause for concern. Rather, it is a very normal and annual response for tuliptrees to hot and dry conditions in the summer months.

The tree is attempting to conserve its water supply, so proper watering practices can help prevent leaf drop. Most water absorption happens around the drip line of the tree, so that’s where watering efforts should be focused. Occasional, long soaks are particularly beneficial to the tree, rather than more frequent short bursts of watering. Most lawn irrigation systems moisten only the top couple inches of soil and do not reach tree roots, so deeper watering with a hose or buckets of water may be necessary to correct tuliptree leaf drop symptoms. Properly mulching will also help hold more moisture in the soil.

Pale yellow marks that mature to large black spots with a leathery appearance on the surface of maples leaves are indicative of maple tar spot. Symptoms of maple tar spot manifest in the summer and heavily spotted leaves may drop earlier than usual.

It’s very prevalent, but not especially harmful to a tree’s health. In fact, it’s generally viewed as just a cosmetic issue and is not treated in any way.

Removing all fallen leaves from affected maples in autumn may reduce the prevalence of maple tar spot in subsequent years. Though, if there are several other trees with maple tar spot in the area, the impact of this thorough clean-up is likely to be minimal, and therefore may not be worth the effort.

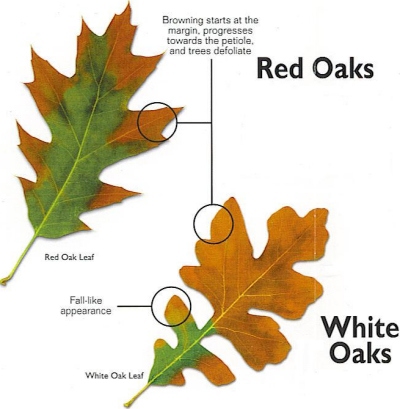

Oak wilt is a major disease of oaks (Quercus spp.) in Michigan. The fungus, Ceratocystis fagacearum causes the disease by invading the vascular system of the tree. The pathogenic (disease) fungus causes the leaves on the tree to wilt. Wilting is followed by rapid death of trees in the red oak family. In the white oak family, death is usually limited to one or more branches of a tree.

Oak wilt in Michigan may infect red, black, scarlet and pin oaks in the red oak family as well as white, swamp, and bur oaks in the white oak family. The pathogenic fungus may infect the trees when an insect carries the fungus to a recent wound. Alternatively the fungus may infect a healthy tree through the roots, if the roots are grafted onto roots of a nearby infected oak of the same species. Leaves of red oaks infected with oak wilt begin to turn reddish-to-bronze in color at the edges. The leaves may wilt and curl, then fall to the ground, or they may turn dark brown and remain attached to the branches. Some leaves drop before wilting begins. These leaves are usually greenish and lie stiff and flat on the ground. Wilting generally occurs in July, beginning at the top of the tree and progressing uniformly downward. Many red oaks die after wilting.

Leaves of red oaks infected with oak wilt begin to turn reddish-to-bronze in color at the edges. The leaves may wilt and curl, then fall to the ground, or they may turn dark brown and remain attached to the branches. Some leaves drop before wilting begins. These leaves are usually greenish and lie stiff and flat on the ground. Wilting generally occurs in July, beginning at the top of the tree and progressing uniformly downward. Many red oaks die after wilting.

White oaks infected with oak wilt generally have leaves that become tan colored and necrotic (dead). Wilting begins from the tip and progresses through the length of the leaves; no distinct line is evident between the necrotic tissues and green tissues. Usually only a few of the branches on an infected white oak will wilt, and on these branches the leaves curl, remaining attached to the tree. Leaf symptoms generally are evident in July.

Trees should be protected from wounding in the springtime; in Michigan, oak trees should not be pruned from March through the end of July, and if possible, all pruning should wait to happen until November. A tree has a moderate risk of contracting Oak Wilt between August and October.

This disease is caused by a fungus, which requires trees from two different families to complete its lifecycle. Trees in the Rosaceae family (like crabapple, hawthorn, and pear species) that get infected develop leaf spots that start as a pale yellow, then range from bright orange to bright red.

Meanwhile, trees in the Cupressaceae family (like eastern redcedar and juniper species) that become infected develop slimy, tentacle-like projections that are bright orange in moist conditions and more bronze when dry.

Cedar-apple rust and other similar rust diseases do not typically cause long-term harm to species in either of the two affected families. Therefore, chemical controls are generally not recommended for this cosmetic issue.

The best way to limit cedar-apple rust infection is by not planting two host species in close proximity to one another. Infected branches can also be pruned away during dry weather, when the fungal spores are less likely to disperse and get established on new branches.

The invasive beech leaf disease was first detected in Michigan in July 2022 and has since been found in several areas across the state—including Oakland County. The disease is associated with a microscopic nematode called Litylenchus crenatae, which overwinters in the leaf buds of beech trees. The damage caused by beech leaf disease can kill afflicted trees within 6-10 years of initial symptom onset.

Symptoms manifest as characteristic dark bands between leaf veins on beech leaves. These dark bands can be seen on both green and brown leaves. Trees lose leaves and undergo dieback as the disease progresses.

Because the disease was only recently detected in Michigan, it’s very important that trees affected with beech leaf disease be reported. It’s also vital that beech tree material (firewood, leaves, nursery stock, etc.) not be moved from areas with known infestations to help prevent spread of the disease.

Beech bark disease has already been detected in Michigan, though it has primarily been seen affecting trees in the Upper Peninsula to date. It can kill trees within just a few years of infestation setting in and large, mature trees tend to be more susceptible to damage.

Beech bark disease has already been detected in Michigan, though it has primarily been seen affecting trees in the Upper Peninsula to date. It can kill trees within just a few years of infestation setting in and large, mature trees tend to be more susceptible to damage.

The disease is spread via sap-sucking insects called scale, which latch onto the woody parts of trees and pierce through the bark to feed on the tree’s sugary sap. The piercing mouthparts allow a neonectria fungus to infiltrate the tree’s vascular system, which blocks the flow of water and nutrients throughout the tree.

The scale is covered in white fuzz, which gives infested portions of beech trees a characteristic woolly appearance. During a tree’s decline, wood may weaken at points of the trunk causing the tree to fail, even though it may still be leafing out with the appearance of health. This is referred to as “beech snap.”

NOTE: One common look-alike that may be confused with beech bark disease-causing scale are white, fuzzy aphids which may feed on beech. Like the scale, they feed on tree sap by piercing the bark, but do not introduce the neonectria fungus. They can be distinguished by their habit of “dancing” when threatened—they sway their abdomens if approached.

Dutch elm disease (DED) is caused by an invasive fungal pathogen, which is spread by elm bark beetles and root grafts. It causes wilting and tree death in all elm species native to Michigan by blocking the tree’s vascular tissues.

The first symptoms generally manifest as leaves on upper branches wilting and yellowing in the summer well before regular autumnal leaf shed. Eventually branches die back and additional parts of the tree are affected until the tree dies.

Tree mortality can be prevented if an infection is caught early and affected branches are pruned away. When pruning an elm afflicted with DED, tools should be regularly sanitized between cuts to prevent the spread of infection to different trees or different parts of the same tree. Systematic fungicides can also be injected into trees to protect them against the disease.

DED was first detected in southeast Michigan in the 1950s. At that time, American elms (Ulmus americana) were very popular as street trees, so they cast their shade on much of Detroit and its suburbs. Nearly all of those elm trees were dead within the next several years as DED quickly spread.

Since then, much effort has gone into developing disease-resistant cultivars of American elms—generally through crossbreeding American elms with Asiatic or European species that are more resistant to DED. Many disease-resistant American elm cultivars are now easily available and commonly planted in Novi, but planting for species diversity has become a much heavier focus to create a more resilient urban forest overall.

There are several diseases and pests that affect the spruce species found in Michigan, but for a variety of reasons, spruce trees appear to be increasingly affected in recent years—and the oft-planted Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens) seems to be bearing the worst of the damage.

There are a handful of major pests and diseases that can lead to spruce decline, but a tree afflicted with one factor can become weakened and more susceptible to other stressors. Therefore, affected trees are commonly impacted by multiple maladies all contributing toward the tree’s decline. Some of the primary spruce decline contributors are:

- Needlecast Diseases – Various needlecast fungal pathogens, with Rhizosphaera being the most notable in this area, may infect and kill off needles on spruce trees. Once killed, the needles, will begin falling off the tree, but needlecast alone generally does not kill trees unless many years of infection and defoliation occur. Needlecast diseases generally attack the previous year’s growth of needles and will produce small black fruiting spores on needles, which can serve as a diagnostic aid.

- Cytospora Canker – Another fungal pathogen known as Cytospora canker causes dieback in the lower branches of trees. Over a period of years it may gradually work its way up the tree killing off additional branches. Needles will typically turn purplish-brown before they fall off and the namesake cankers will normally be located close to the trunk on dead, infected branches. The cankers may be coated in resin expelled from the tree.

- Phomopsis Canker – This fungus was long thought to primarily affect young spruce growing in nurseries or Christmas tree farms, but it has now become more common to find Phomopsis canker stressing mature spruce trees and is a key contributor toward spruce decline. It can cause defoliation, loss of branches, or even tree death as cankers form on older branches—usually lower in the tree first. On more mature trees, Phomopsis kills off branches from the trunk to the branch tip, meaning the tips of the branches are affected last.

As with all tree species, a stressed spruce tree is more susceptible to the diseases listed above, and a variety of other potential problems. Tree caretakers can greatly improve a spruce tree’s ability to resist diseases and pests by ensuring they’re provided good growing conditions.

For example, each of the above are caused by a fungal pathogen, which thrive in moist conditions and in areas where air circulation or sun exposure are insufficient. If spruce trees are being irrigated excessively, hit directly with sprinkler spray, or were planted too close together for screening purposes, then they’ll be much more susceptible to these fungal issues. A tree’s overall vigor can also oftentimes be boosted by improving soil conditions through aeration or prescribed fertilization to target identified nutrient deficiencies.

Spruce branches infected with one of the aforementioned diseases should be pruned away during a dry time of year, when fungal spores are less likely to spread.

Several pines trees abundantly growing in Michigan, including austrian, scotch, and red pines, are susceptible to a fungal pathogen called Diplodia tip blight. The disease affects the current year’s growth of needles and can cause branch dieback or even tree death if infection persists through multiple years.

Several pines trees abundantly growing in Michigan, including austrian, scotch, and red pines, are susceptible to a fungal pathogen called Diplodia tip blight. The disease affects the current year’s growth of needles and can cause branch dieback or even tree death if infection persists through multiple years.

Because the disease affects the current year’s growth, dieback will first appear at the tips of branches. Small, black fruiting bodies also appear on infected needles—especially under the papery sheath at the base of the needles. If both of these conditions are present, the tree is very likely afflicted with Diplodia tip blight. The disease is most often found on very old trees or stressed trees growing in conditions not well suited to their needs.

Like most fungal pathogens, Diplodia tip blight prospers in moist environments. Ensuring sprinkler systems aren’t hitting susceptible trees directly, sanitization pruning to remove infected branches while increasing air movement and sun exposure, and boosting overall tree vigor through good tree care practices will help reduce the impact of the disease.

The fungus overwinters on multiple parts of the tree, so it’s very difficult to eradicate the disease completely once it’s established. Slowing disease advancement with plans to eventually replace the susceptible tree with more resistant species is a more common management strategy.

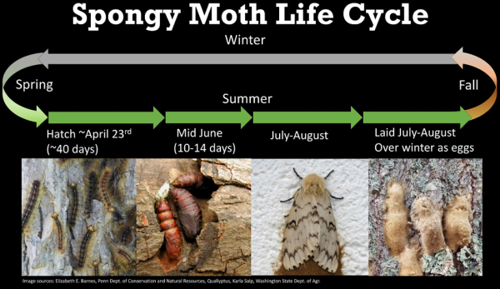

The spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) is one of the most notorious pests of hardwood trees in the Eastern United States. Since 1980, it has defoliated close to a million or more forested acres each year. In 1981, a record 12.9 million acres were defoliated.

In wooded suburban areas, during periods of infestation when trees are visibly defoliated, larvae crawl up and down walls, across roads, over outdoor furniture, and even inside homes. During periods of feeding they leave behind a mixture of small pieces of leaves and “frass,” or excrement.

Spongy moth infestations alternate between years when trees experience little visible defoliation (moth population numbers are sparse) followed by 2 to 4 years when trees are visibly defoliated (moth population numbers are dense).

Spongy moth is not a native insect. It was introduced into the United States in 1869 by a French scientist living in Massachusetts. The first outbreak occurred in 1889. By 1987, it had established itself throughout the Northeast. The insect has spread south into Virginia and West Virginia, and west into Michigan. Infestations have also occurred in Utah, Oregon, Washington, California, and many other States outside the Northeast.

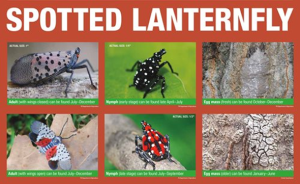

The spotted lanternfly (SLF), an invasive insect native to east Asia, was first found in the U.S. in 2014 in Pennsylvania. It has since spread to several other states. It feeds on a wide variety of plants, including economically important species like cherry trees, apple trees, grapevines, and several hardwood trees like oaks and maples. The insects weaken trees by sucking sap from stems and branches, then they excrete a significant amount of honeydew—a sticky product of their feeding behavior that can cover surfaces on and below the tree.

The spotted lanternfly (SLF), an invasive insect native to east Asia, was first found in the U.S. in 2014 in Pennsylvania. It has since spread to several other states. It feeds on a wide variety of plants, including economically important species like cherry trees, apple trees, grapevines, and several hardwood trees like oaks and maples. The insects weaken trees by sucking sap from stems and branches, then they excrete a significant amount of honeydew—a sticky product of their feeding behavior that can cover surfaces on and below the tree.

Honeydew oftentimes promotes fungal and bacterial growth, which can further damage the tree and other nearby surfaces. As a planthopper, the SLF can only move relatively short distances on its own. However, it can be spread great distances and infest new areas with help from human activity. It lays egg masses on many outdoor surfaces ranging from trees, to vehicles, to camping gear. These egg masses, or the insects themselves, can then be transported elsewhere if people aren’t carefully monitoring for them. Because this is an invasive species, our native plants are more susceptible to their attacks and there are few native predators to keep the SLF population in check.

Consequently, many parts of the eastern United States where SLFs are established are overrun with the pest. Novi residents can help protect the City’s urban forest by monitoring for SLF in its various life stages - especially when traveling through areas where it is known to exist.

The invasive Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) has been discovered attacking trees in parts of Ohio, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York.

The invasive Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) has been discovered attacking trees in parts of Ohio, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York.

Tunneling by beetle larvae girdles tree stems and branches and repeated attacks lead to dieback of the tree crown eventual death of the tree.

ALB most likely travelled to the United States inside solid wood packing material from China. The beetle has been intercepted at ports and found in warehouses throughout the United States.

This beetle is a serious pest in China, where it kills hardwood trees in roadside plantings, shelterbelts, and plantations. In the United States the beetle prefers maple species (Acer spp.), including boxelder, Norway, red, silver, and sugar maples. Other preferred hosts are birches, Ohio buckeye, elms, horsechestnut, and willows. Occasional to rare hosts include ashes, European mountain ash, London planetree, mimosa, and poplars. A complete list of host trees in the United States has not yet been determined, but it is expansive.

ALB populations have been eradicated through the targeted removal of infested trees in New York, Chicago, and Toronto, but early detection of the pest was integral to those successes. The showy presence of the adult beetle and the large, conspicuous egg pits and circular emergence holes on the trunk, which are about the same diameter as a pencil, help with identification of the pest.

Multiple caterpillar species that munch on hardwood tree leaves spin webs between branches to create their signature “tents.” These are frequently seen in trees along roadsides.

As trees are defoliated by hungry caterpillars, they can be weakened—especially in the presence of a heavy population density. However, trees are rarely weakened to the point of death and are much more likely to fully recover in time.

The web tents can be removed, preferably during cloudy or rainy conditions when more of the caterpillars are inside the web, to reduce caterpillar populations and limit tree damage. Use of insecticides is generally not recommended for this pest.

Emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, is an exotic beetle that was discovered in southeastern Michigan near Detroit in the summer of 2002. It probably arrived in the United States on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or airplanes originating in its native Asia. Because ash trees (Fraxinus sp.) in North America have no immunity to the insect, EAB wiped out millions of ash trees in Michigan.

Emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, is an exotic beetle that was discovered in southeastern Michigan near Detroit in the summer of 2002. It probably arrived in the United States on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or airplanes originating in its native Asia. Because ash trees (Fraxinus sp.) in North America have no immunity to the insect, EAB wiped out millions of ash trees in Michigan.

Adult EABs are metallic green in color and approximately 1/2 inch in length. Larvae are cream-colored and are found in or under the bark.

There are several indicative signs of emerald ash borer infestation. Initial thinning and/or yellowing of the foliage and development of excessive suckers from the trunk or branches are earlier signs. Small, D-shaped emergence holes on the trunks or branches will indicate that larvae have been active in the tree, and removal of some outer bark may reveal “S tunneling.” Eventually, infested trees will die.

The City of Novi Forestry Division took a proactive approach in managing the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) by monitoring our street ash tree population in the early 2000s. In July of 2003, we completed a comprehensive inventory of the city’s streetside ash trees, which then numbered approximately 2,500. The purpose of this inventory was to assess the health and maintenance needs of the ash trees. Unfortunately, forestry crews began actively removing ash trees on public property throughout Novi in hopes of slowing the spread of EAB, but infestations were already popping up across the state.

The main takeaway message from the devastation that EAB wrought is that tree diversity is the key to a healthy and sustainable urban forest. The City of Novi has been planting a wide diversity of tree species in an effort to prevent similar fallout in the future. Rows of the same tree species lining streets are no longer desirable. Areas where the same tree species are spaced closely together make it easier for insects and diseases to spread.

The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) is an invasive insect that attacks Michigan’s native eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) trees. Already established in eastern states, HWA poses a significant threat to the ~170 million hemlock trees growing in Michigan forests and landscapes.

The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) is an invasive insect that attacks Michigan’s native eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) trees. Already established in eastern states, HWA poses a significant threat to the ~170 million hemlock trees growing in Michigan forests and landscapes.

The pests feed on the tree at the base of its needles, where the needles attach to woody shoots. As they feed on the nutrients within the trees’ needles, the HWA secretes a white, waxy substance for protection. This characteristic waxy substance is most notable from late fall to early summer and usually seen on the undersides of shoots, which can help identify an infestation.

Symptoms begin as dieback and at times a gray-green coloration of the needles. Infestations can kill eastern hemlock trees in as little as 4-10 years. Suspected HWA infestations should be reported and, if confirmed, treatment with approved insecticides should follow. Hemlock tree materials (firewood, needles, etc.) should not be moved in order to limit the spread of the invasive pest.

The woodwasp, Sirex noctilio, and the associated pathogenic fungus, Amylostereum areolatum, are native to Eurasia and North Africa and have been introduced in New Zealand, Australia, South America, and North America.

The woodwasp, Sirex noctilio, and the associated pathogenic fungus, Amylostereum areolatum, are native to Eurasia and North Africa and have been introduced in New Zealand, Australia, South America, and North America.

The woodwasp is now present across much of New York State, parts of Ontario, and neighboring areas such as eastern Michigan, northern Pennsylvania, and a few counties in Ohio and Vermont. In the upper Midwest, the two could jeopardize decades of careful management of Jack pine (Pinus banksiana) stands aimed at ensuring survival of the highly endangered Kirtland's warbler. Federal and state agencies spend about $2.5 million annually to manage jack pine stands in Michigan that benefit the warbler.

The woodwasp injects fungus in the tree when the female lays her eggs. The larvae of this exotic pest are responsible for damaging the tree. It severs the trees' conductive tissues, interrupting the transport of water and nutrients. Adult females lay their eggs in two- and three-needled pine trees, including: Austrian, jack, red, and Scotch pines.

Sirex Woodwasp is not expected to significantly impact healthy landscape pine trees in the state. Its impact on vigorous, well managed pine plantations in Michigan, while not yet fully defined, is likewise not anticipated to be severe.